Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

Blog

-

Object Destructuring in Javascript

In javascript, objects are commonly used to store multiple data in a single variable. This provides a very compact and convenient way to operate on the data, especially, when passing the data to other parts of the application code. Javascript provides a very convenient means to extract the value of each data when needed.

In Javascript, we can use the object destructuring method to extract the values of multiple properties from an object in just a single statement. It eliminates the need to for multiple statements when accessing the values of multiple object properties. The object destructuring approach has less typing and saves time.

Javascript object destructuring can also be used to perform other object operations such as cloning, extending, updating, and merging other objects.

This post takes an in-depth look at ES6 Javascript object destructuring technique, with emphasis on clarity and working examples for better understanding.

Table of Contents

- Object Destructuring Assignment

- Object Destructuring Assignment Syntax

- Understanding Object Destructuring

- Mismatch Variable Name in Property Keys is undefined

- Setting Default Values

- Destructuring into Declared Variables

- Aliasing Declaration Variables

- Extracting Rest of Properties Into a Variable

- Using Spread Syntax in Object Destructuring

- Destructuring Function Parameters

- Destructuring Nested Objects

- Summary

Object Destructuring Assignment

In Javascript, object destructuring assignment is an expression that makes it possible to extract some or all properties of an object into specific variables. It was introduced in ES6 (ECMAScript 2015) as a means to simplify the extraction of properties from objects and arrays. It can also be used to destructure strings.

Before its introduction, we would extract the values of object properties by typing the name of the object variable followed by the dot (

.) operator, and then the property we want to access.For example, let’s suppose we have an object data that contains information about a user:

JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' };We can access the values of the object properties using the dot (

.) notation:JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; // extract values const name = User.name; const email = User.email; const role = User.role;Another approach involves specifying the property names as a string enclosed in square brackets,

[], following the property name:JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; // extract values const name = User['name']; const email = User['name']; const role = User['name'];Both approaches, however, involve more typing to access property values. For example, each access to a property value requires its own statement. Additionally, we always need to type the object variable name, square brackets, and property name in each statement to access a property value. All these lead to more typing, especially when we have to access multiple object property values.

But ES6 Javascript has a better and compact approach to do this, called object destructuring. With ES6 Javascript object destructuring, we can extract all or some of the property values of the

Userobject in just a single statement:JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; // extract values const { name, email, role } = User;Line 9 in listing 4 does the trick. It is called object destructuring assignment. In just a single statement, we have been able to extract all the property values that we need. We did not have to type multiple object variable name, square brackets, and property keys. This approach is much of less typing and saves time.

In the discussions that follow, we will delve deeper into Javascript object destructuing. Before that, we should look at the very basic syntax of Javascript object destructuring assignment.

Object Destructuring Assignment Syntax

In Javascript object destructuring assignment, an object from which we want to extract property values is assigned to declared variables. The declaration variables into which the values of the object properties are stored are enclosed in braces,

{}, on the left-hand side of the assignment operator.For example, in listing 4, the statement on line 9 is object destructuring assignment. In this assignment, the

Userobject is destructured into individual properties, and the values of these properties are assigned to the declaration variables enclosed in curly braces.Unlike in Javascript array destructuring, the order of the declaration variables is not important in object destructuring. Shortly, we will know how Javascript is able to tell which property values to store in each of the declaration variables.

Looking again at line 9 in listing 4, we can tell that an object destructuring assignment has the following basic syntax:

JavaScript// destructure object into variables let { var1, var2, var3 } = ObjectDataIn this assignment syntax,

var1,var2, andvar3are declaration variables into which the values of properties inObjectDatawill be stored. As seen, the declaration variables are enclosed in braces,{}. This is in contrast to array destructuring assignment syntax, which uses square brackets,[], to enclose declaration variables.We can even use the

constdeclaration keyword for the declaration variables:JavaScript// destructure object into variables const { var1, var2, var3 } = ObjectDataUnderstanding Object Destructuring

Javascript object destructuring is a programming technique that makes it possible to extract multiple object property values into variables a single statement. It eliminates the need for dedicated statements for each property value access, and has less typing than property access with the dot notation.

What makes this approach so handy is that we can declare multiple variables and use the object variable name only once in an assignment. Javascript does the job of extracting the property values into these declared variables.

Consider the code listing below:

JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' };With Javascript ES6 / ECMAScript 2015, we can extract muiltiple properties into variables in just a single statement whiles using the

Userobject name only once in an assignment:JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; // extract property values into variables const { name, email, role } = User; console.log(name); // output: Daniel console.log(email); // output: dan@mail.com console.log(role); // output: DeveloperThe order of the variables in the declaration does not matter. We can declare the target variables in any order:

JavaScript// extract property values into variables const { role, name, email } = User; console.log(name); // output: Daniel console.log(email); // output: dan@mail.com console.log(role); // output: DeveloperIf the order of the declaration variables does not matter, then how is Javascript able to map the declaration variables to the object properties and extract their values? The answer is simple. By default, Javascript expects the declaration variable names to match property keys in the object being destructured.

For example, in the object destructuring statement,

JavaScriptconst { name, email, role ] = User;the declared variable

name,email, androlematch property key names in theUserobject.JavaScriptconst User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' };By this, Javascript is able to map the variable names to the object property keys and extract their values. Later, we will see how we can specify variable names that are not property keys in the object being destructured.

Remember from our discussion on destructuring assignmnent syntax that we use braces,

{}, to declare target variables when destructuring an object. By default, the variable names enclosed in the braces are the names of the properties that we want extract.If a variable name exists in the destructuring declaration but is not found as a property or key in the object being destructured, then the value for that variable will be

undefined. We delve more into this next.Mismatch Variable Name in Property Keys is

undefinedWe have indicated that, in object destructuring, the variable names in the destructuring declaration should match property keys in the the object that is being destructured. We have already seen this in listing 8.

But what if we type a declaration variable name which does not exist as a key in the properties of the object being destructured? Well, let’s see what happens.

JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; const { username, email, role } = User; // log values console.log(username); // output: undefined console.log(email); // output: dan@mail.com console.log(role); // output: DeveloperOn line 8, the

usernamevariable in the declaration variables does not match any name in theUserobject property keys. The remaining declaration variable names,emailandrole, however have matching names in theUserobject property keys.Since

usernamedoes not match any property key in theUserobject, there will be no value to extract into theusernamevariable. Therefore its value will beundefined, as seen in its output on line 11.Thus, if variable name in the destructuring declaration is not found as a property key in the object being destructured, then the value of that variable will be

undefined.Setting Default Values

If there is a possibility for the value of a property to be

undefined, then we can set a default value that should be used. We do this by assigning the default value to the target variable in the destructuring statement. The following listing is an example:JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: undefined }; const { name, email = 'user@mail.com', role = 'Data Analyst' } = User; // log values console.log(name); // output: Daniel console.log(email); // output: dan@mail.com console.log(role); // output: Data AnalystOn line 6, we have deliberately set the value of the

roleproperty toundefined. In the variables declaration online 8, we have set default values foremailandrole. After object destructuring, we can see from the log values that the default value forrolehas been used since the extracted value from theroleproperty in theUserobject isundefined.The default value for the variable

email, which isuser@mail.com, was not used since theemailproperty of theUserobject is notundefined. Thus, the default value is used when the value extracted from an object property isundefined.Destructuring Into Existing Variables

In the examples that we have covered so far, we have extracted the property values into newly declared variables:

JavaScript// delcare variables const { name, email, role } = User;The

constkeyword preceding the declaration variables is an indication that we are declaring new variables.If we have existing variables whose names match property key names in the object, then we can specify the existing variables in the destructuring statement. In this case, there will be no need to precede the destructuring statement with

constorlet. However, there is one more thing to take into account. We will need to enclose the whole statement in parenthesis before that will work:JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; // variables declration let name, email, role; // destructure object into the existing variables ({ name, email, role } = User);The variables

name,email, androleare declared on line 9. Then on line 12, we specify these existing variables in the destructuring statement. You should observe that we have enclosed the destructuring assignment in parenthesis,(). Without the parenthesis, an error will be generated.For example, the following statement destructures the User object into existing variables without the statement being enclosed in parenthesis:

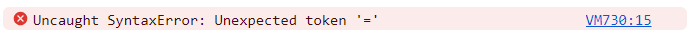

JavaScript// destructure object into the existing variables { name, email, role } = User;Destructuring an object into existing variables without the statement being enclosed in parenthesis, like on line 2, will generate the following error:

If we intend to destructure an object into already declared variables, we will need to enclose the destructuring assignment expression in parenthesis,

().Aliasing Declaration Variable Names

In listing 8, we understood that, by default, we are compelled to declare variables with names that match object property key names when destructuring an object. If a variable name in the declaration does not match a property key in the object being destructured, its value will be

undefined.But what if the object property keys are not descriptive enough to be used as variables in the current scope? Or what if we prefer a different name for the variable?

Consider the following object data:

JavaScript// object declaration const User = { n: 'Daniel', e: 'dan@mail.com', r: 'Developer' }Some applications that transmit data through networks use shortened names rather than descriptive and long property key names. The aim may be to reduce the size of data transmitted over the network.

If we are to destructure an object with non-destructive property keys, such as in listing 16, by default, we will be compelled to use these non-descriptive property keys as variables in the application.

JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { n: 'Daniel', e: 'dan@mail.com', r: 'Developer' }; const { r, e, r } = User; // log values console.log(name); // output: Daniel console.log(email); // output: dan@mail.com console.log(role); // output: DeveloperLuckily, ES6 Javascript allows us to specify alias names for object property keys. We can use these alias names to refer to the properties in the object being destructured.

To specify an alias name when destructuring an object, we separate the declaration variable name and the alias name with a colon,

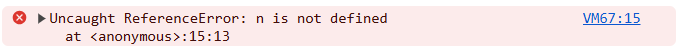

:. For example:JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { n: 'Daniel', e: 'dan@mail.com', r: 'Developer' }; const { n: name, e: email, r: role } = User; // log values console.log(name); // output: Daniel console.log(email); // output: dan@mail.com console.log(role); // output: DeveloperOnce an alias name is specified, we cannot use the actual variable name in the application logic. For example, the following will generate an error:

JavaScriptconsole.log(n);This produces a

ReferenceError. Since we have specified an alias name for the variablen, we can no longer use it in the application scope where it is declared. To Javascript, such variable does not exist:

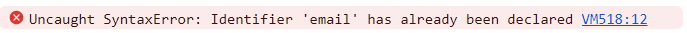

A problem arises if a property that needs to be extracted has the same name as a variable already declared in the current scope. Consider the following code listing:

JavaScript// email variable declration let email = 'default@mail.com'; // initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; // extract values from the User object const { name, email, role } = User;This code listing will generate a syntax error when run. A sample error can be seen below:

The

Userobject contains a property with the keyemail. Meanwhile, in the destructuring assignment on line 12, the declaration attempts to create variables, includingemail, Butemailis an existing variable declared on line 2. This generates the syntax error since a variable with nameemailalready exists.The solution to such problem depends on whether we can overwrite the value in the existing variable,

email, or not.If we do not want to overwrite the value in the existing variable, then we will need to provide an alias name for the

emailproperty:JavaScript// extract values from the User object const { name, email: userEmail, role } = User; // log values console.log(email); // output: default@mail.com console.log(userEmail); // output: dan@mail.comHowever, if we wish to overwrite the value in the existing variable,

email, then we will need two statements to extract the values: one to declare the new variables for assignment, and the other to assign to the existing variable:JavaScript// extract into existing variable ({ email } = User); // extract into new variables const { name, role } = User;Since

emailis already declared, we only perform the assignment by enclosing the statement in parentheses. However,nameandroleare new variables and therefore we declare them with theconstkeyword. We could also have usedletorvarto accomplish same.Extracting Rest of Properties into a Variable

Sometimes, we may wish to extract the values of some properties into specific variables and then pack the rest, or remaining properties into another variable. ES6 Javascript provides the rest operator to do this.

The rest operator is a three consecutive dot (

...) operator that is used to precede a declaration variable name to signify that the remaining properties that have not been extracted yet, should all be extracted and packed into the variable preceded by the rest operator.For example, if we want to extract the

nameproperty into a variable and extract the remaining properties into another variable, we will have to use the following destructuring statement:JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; const { name, ...theRest} = User; console.log(name); // output: Daniel console.log(theRest); // output: { email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }On line 8, the value of the

nameproperty of theUserobject is extracted into thenamedeclaration variable. The rest operator, (...), precedingtheRestvariable implies that, the remaining properties which have not been extracted yet should all be extracted and packed intotheRestvariable.With the rest operator preceding

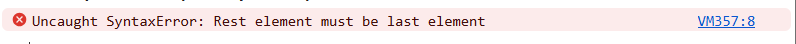

theRestvariable, Javascript packs the remaining properties into the variable for us. One important thing to note is that the variable preceded with the rest operator must be the last element in the declaration variables. The following statement is wrong and will generate a syntax error:JavaScriptconst { ...theRest, name } = User;The following syntax error will be generated since the rest operator is applied to a variable element which is not the last:

Another important thing to note is that, the variable into which the properties are packed is always an object. This is so even if there is only one property packed into it. Let’s see an example below:

JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; const { name, email, ...theRest} = User; // log value of theRest console.log(theRest); // output: { role: 'Developer' }On line 8, we apply the rest operator to

theRestvariable. At this point, thenameandemailhave already been extracted, with onlyroleremaining and packed intotheRest. The log on line 11 reveals thattheRestis actually anobject, although only one property was extracted into it. Thus, if we precede a declaration variable with the rest operator, then thetypeof the variable is always anobject.Using Spread Syntax in Object Destructuring

The spread syntax is ES6 Javascript expression that expands the properties of an object into individual parts. Like the rest syntax, the spread syntax is a three consecutive dot

(...) operator preceding an object variable that expands the properties of the object.The spread syntax can be used to perform operations such as merging multiple objects, cloning, updating, and extending an object.

Cloning Objects

The ES6 Javascript spread syntax can be used to make a shallow clone of an object so that an update to one object reference does not affect the other object.

Suppose we have the following object data:

JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' };If we assign the

Userto another variable, both variables will have the same reference to the object data.JavaScript// assign the User object to another variable const anotherUser = User; console.log(anotherUser === User); // output: trueIn this case, an update to the data using one variable will affect the other variable. To make a shallow clone of the

Userobject so that they will have the same data but different references, we will need to clone theUserobject.With ES6 Javascript, we can use the spread syntax to clone the

Userobject.JavaScript// make a copy of the User object const anotherUser = {...User};The spread operator expands the properties of the

Userobject and places them between the braces,{}. This creates a new object with a different reference, and the newly created object is assigned toanotherUser.Although

UserandanotherUserhave the same data values, they have different references, and an update to one does not affect the other. Thus, we can use the ES6 Javascript spread syntax to clone an object.Extending Objects

We can use the ES6 Javascript spread syntax to extend an object. This is particularly helpful if there are multiple properties to be added to an existing object data.

In the pre-ES6 era, we could do this by using the dot (

.) notation to extend an object with new properties, or useObject.assign()to add new properties:JavaScript// initialize an object let data = { name: 'Daniel' }; // add new properties data.email = 'dan@mail.com'; data.role = 'Developer';The following code listing uses the spread syntax to extend an existing object:

JavaScript// initialize an object let data = {}; // add new properties data = { ...data, email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' };Line 5 initializes a new object by spreading or expanding the current properties of

data, and then includesemailandroleproperties in the new object. In this example, we assign the newly initialized object todata. Sometimes, we may need to assign the newly initialized object to a different variable.Updating Objects

Although we can use the dot (

.) notation to update object property values, if we need to update multiple values, we will need multiple statements to do this:JavaScript// initialize object data let User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; // update property values with dot notation User.name = 'Emmanuel'; User.email = 'emma@mail.com';Before ES6 Javascript, we could also achieve this in a single statement using

Object.assign()method. However, we can use the spread syntax to achieve the same in just a single statement:JavaScript// initialize object data let User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }; // update property values with dot notation User = { ...User, name: 'Emmanuel', email: 'emma@mail.com' }; console.log(User); // output: { name: 'Emmanuel', email: 'emma@mail.com', role: 'Developer' }Merging Objects

If we have multiple objects that we need to merge into one object, we can easily do so using the Javascript spread syntax. To do this, we will need to initialize a new object and spread the properties of the objects that we need to merge in the initializer object.

For example, suppose we have the following objects,

AandB:JavaScript// Object A const A = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com' }; // object B const B = { role: 'Developer', address: { city: 'Kumasi', region: 'Ashanti' } }We can merge objects

AandBinto another object using the spread syntax. To do this, we spread the properties of objectsAandBin a new object that we initialize:JavaScript// merge A and B into a new object const User = { ...A, ...B }; // log User object console.log(User);From the log output below, we can see that the

Userobject contains all the properties of objectsAandB:

The properties of objects

AanBwere merged into theUserobject.Destructuring Function Parameters

ES6 Javascript provides a very convenient way to destructure object parameters in a function. That is, we can destructure function parameters that are objects.

Before ES6 Javascript, we would access object properties from function parameters such as in the following code listing:

JavaScriptfunction showUser(userParam) { let name = userParam.name; let email = userParam.email; let role = userParam.role; // log values console.log(name); // output: Daniel console.log(email); // output: dan@mai.com console.log(role); // output: Developer }Rather than access the property values into new variables, we can destructure and bind the parameter object properties into new variables directly in the function header: To understand this better, we should understand that when we pass a value to a function, the argument value is assigned to the function parameter.

Given the

Userobject used in earlier examples, we can pass it to theshowUserInfo()function as follows:JavaScriptshowUserInfo(User);As indicated earlier, passing a value to a called function assigns the function argument to the function parameter, as if we have done the following:

JavaScriptuserParam = User;userParamis the parameter variable in the function header, andUseris the object passed as argument. But sinceUseris an object, we can destructure it into defined variables, as we have already been doing, as follows:JavaScript{ name, email, role } = User;With ES6 Javascript, we can replace

userParamin the function header with the declaration variables{ name, email, role }. Thus, we can rewrite theshowUserInfo()function as follows:JavaScriptfunction showUserInfo({ name, email, user }) { // log values console.log(name); // output: Daniel console.log(email); // output: dan@mai.com console.log(role); // output: Developer }As can be seen, destructuring object parameters in function headers has less typing and saves time.

Destructuring Nested Objects

We can extend the understanding gained so far in Javascript object destructuring to destructure objects nested within an object. Destructuring nested objects is simple, although it may seem challenging at first.

Let’s revisit our

Userobject data which we have used for the examples in previous discussions:JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer' };We will extend this

Userobject by adding anaddressproperty:JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer', address: { city: 'Kumasi', region: 'Ashanti' } };We can identify that the value of the

addressproperty is an object. Thus, we have an object within an object. Let’s suppose that we want to extractcity, andregioninto variables.In the pre-ES6 Javascript era, we could extract the

cityandregionfrom theaddressproperty using the dot notation, such as in the following code listing:JavaScript// extract city and region let city = User.address.city; let region = User.address.state;With ES6 Javascript object destructuring, we can extract these values into variables in just a single statement. We will take step by step approach to better understand nested object destructuring.

When destructuring a nested object, we need to specify the property key name followed by colon,

:, then the declaration variables enclosed in braces:JavaScriptconst { nestedObjectProperty: { DECLARATION_VARIABLES }};Think of the specification of the property key name as directing Javascript to the nested object which we want to destructure.

For example, in our

Userobject in listing 41, the nested object has the property key nameaddress, hence we will specify this property key name, followed by colon, (:), then the declaration variables:JavaScriptconst { address: { DECLARATION_VARIABLES }} = User;One key trick in destructuring nested objects is to isolate the nested object to be destructured, whiles taking note of its property key name. In our example, the value of the

addressproperty is an object, and we can isolate theaddressobject as follows:JavaScriptaddress = { city: 'Kumasi', state: 'Ashanti' }Given this

addressobject, we can use our normal destructuring technique to extract the values ofcityandregioninto variables as follows:JavaScriptconst { city, region } = address;As can be seen, destructuring the

addressproperty in isolation gives us{ city, region }, which we can use to replace{ DECLARATION_VARIABLES }in listing 41.JavaScriptconst { address: { city, region }} = User;That is really simple, isn’t it?. The only extra typing here is the specification of the

addressproperty key name. It is however important since this is a clue to Javascript to know which specific nested object to look and extract property values.The following code listing is a working example of what we just covered:

JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer', address: { city: 'Kumasi', region: 'Ashanti' } }; // extract city and region from User object const { address: { city, region }} = User; console.log(city); // output: Kumasi console.log(state); // output: AshantiIn another example, we will attempt to extract

name,email, andcityfrom theUserobject. We should remember thatcityis found in a nested object with property nameaddress, which is found inUserobject.The following statement extracts

name,email, andcityfrom theUserobject.JavaScript// extract name, email, and city const { name, email, address: { city }} = User;Since

nameandemailare not properties in nested object, we do not precede their declaration variables with property key names. However,cityis a property found in a nested object, hence we precede the declaration variable withaddress:. As indicated earlier, this a hint to Javascript to know where to perform the nested object destructuring.Let us consider another example that is also simple to do, but maybe a bit challenging. We will introduce a

locationobject, nested in theaddressobject, which is also nested in theUserobject.JavaScript// initialize object data const User = { name: 'Daniel', email: 'dan@mail.com', role: 'Developer', address: { city: 'Kumasi', region: 'Ashanti', location: { street: 'XYZ Avenue', house: 'P8 BLK5' } } };We have added a

locationobject, spanning from line 9 to line 12, to theaddressobject which is also nested in theUserobject. If we need to extract the values ofname,city, andstreetproperties, the following statement will do:JavaScript// extract name, city, and street const { name, address: { city, location: { street }}} = User; // log values console.log(name); // output: Daniel console.log(city); // output: Kumasi console.log(street); // output: XYZ AvenueLet’s break down the object destructuring statement on line 2 to have a better understanding.

We can identify from the

Userobject in listing 50 that, the value ofnameproperty is basic type, string in this case. Since this is not a nested object, we can extract its value directly without preceding it with a property name:JavaScript// extract name, city, and street const { name, ... } = User;cityis a property found in a nested object with property nameaddress. To extract its value, we need to specify the property key nameaddress, and separating the declaration variable with a colon (:):JavaScript// extract name, city, and street const { name, address: { city } } = User;Lastly, we can identify that the

streetproperty is found in thelocationobject. Sincelocationis a nested object, we will specify its name and the declaration variable as:location: { street }.But

locationis nested inaddressobject. We will therefore need to include it in the declaration for theaddressproperty. Thus, we will have the following destructuring statement:JavaScript// extract name, city, and street from User const { name, address: { city, location: { street }}} = User; // log values console.log(name); // output: Daniel console.log(city); // output: Kumasi console.log(street); // output: XYZ AvenueThe destructuring statement on line 2 extracts

name,city, andstreetfromUser.Summary

Javascript object destructuring is a programming expression that extracts the values of object properties into declared variables. It can be used to extract the values of multiple object properties into variables in a single statement.

JavaScriptconst Student = { id: 1, name: 'Emmanuel', email: 'emma@mail.com' } // extract property values in a single statement const { id, name, email } = Student;By default, Javascript expects the declaration variable names to exist as property keys in the object being destructured. If a declaration variable name does not exist as a property key in the object being destructured, then the value of the variable will be undefined:

JavaScriptconst Student = { id: 1, name: 'Emmanuel', email: 'emma@mail.com' } // extract property values in a single statement const { stdId, name, email } = Student; // log stdId console.log(stdId); // outut: undefinedAs can be seen, the first declaration variable has the name

stdId. However, theStudentobject does not contain a property key with this name. Therefore, the value ofstdIdwill beundefinedsince it does not have a matching property key name in theStudentobject.If we wish to use a different name as variable than the property key name in the object, then we can provide an alias name to be used:

JavaScriptconst Student = { id: 1, name: 'Emmanuel', email: 'emma@mail.com' } // extract property values in a single statement const { id: stdId, name, email } = Student; // log stdId console.log(stdId); // output: 1On line 8, we specify an alias name,

stdId, for theidproperty inStudentobject. The value of theidproperty is extracted intostdId. When we set an alias name, we cannot use the property key as a variable for the same value: An attempt to do this leads to aReferenceError:JavaScript// log id console.log(id); // ReferenceError: id is not definedWhen destructuring an object, we can set default values for variables into which extracted values are saved. The default values are used if the value of the variables are

undefinedafter destructuring.Consider the following code listing:

JavaScriptconst Student = { id: 1, name: 'Emmanuel', email: 'emma@mail.com' } // extract property values in a single statement const { id, name, email, programme } = Student; console.log(programme); // output: undefinedObserve that the fourth declaration variable,

programme, does not exist as a property key in theStudentobject. As we have already indicated, the value ofprogrammewill beundefined. We can specify a default value that should be used rather thanundefinedby assigning the default value to the variable in the destructuring statement:JavaScriptconst Student = { id: 1, name: 'Emmanuel', email: 'emma@mail.com' } // extract property values in a single statement const { id, name, email, programme = 'Pharmacy' } = Student; console.log(programme); // output: PharmacyWe can also apply object destructuring to destructure object parameters in function headers:

JavaScriptfunction show({ id, name, email }) { console.log(name); console.log(email); } show({ id: 1, name: 'Emmanuel', email: 'emma@mail.com' });Other operations that can be performed with Javascript object destructuring include the use of spread syntax to extend, merge, clone, and update objects, as well as pack multiple properties into a single variable with the rest operator.

We can also apply object destructuring technique to destructure nested objects.

-

Array Destructuring in Javascript

Javascript array destructuring, introduced in ES6 Javascript, is a programming technque that makes it possible to extract values from data such as arrays, objects, and strings, into variables. It provides a very concise way to extract multiple values from an array into variables and avoids repetitive array indexing.

Given an array data, we can extract the values of specific array elements and ignore those that we do not need. In addition, we can use array destructuring to easily swap the values of two variables without the need to declare a temporal variable.

In this post, we will demystify Javascript array destructuring and understand how it simplifies array operations such as array concatenation, array cloning, extraction of values from nested arrays, etc.

Table of Contents

- Destructuring Assignment

- Destructuring Assignment Syntax

- Array Destructuring

- Separating Variable Declarations from Assignment

- Variables Unmapped to Initializer Array Elements Are undefined

- Setting Default Values for Variables

- Skipping to Selectively Extract Needed Values

- Swapping Values of Two Variables

- Using Rest Syntax to Assign Remaining Values

- Using Spread Syntax to Expand Array Elements

- Destructuring Array in Function Parameters

- Destructuring Nested Arrays

- Wrapping Up

Destructuring Assignment

In javascript, destructuring assignment is an expression that makes it possible to selectively extract all or part of an array or object data and store them in specific variables in a single statement. In other words, destructuring assignment is an expression that allows for the unpacking of array and object data into variables.

Destructuring assignment was introduced in ES6 (ECMAScript 2015) Javascript. Before its introduction, we normally access the elements of an array by typing the name of the array followed by the index of the element enclosed in square brackets.

For example, let’s suppose we have an array of programming languages, as shown below:

JavaScriptlet languages = ['Javascript', 'PHP', 'Python', 'Java'];In the pre-ES6 era, if we need to extract the array elements into variables, we will need to use array indexing to get the specific elements and store them in variables:

JavaScriptlet languages = ['Javascript', 'PHP', 'Python', 'Java']; // extract array elements into defined variables let var1 = languages[0]; // will contain Javascript let var2 = languages[1]; // will contain PHP let var3 = languages[2]; // will contain Python let var4 = languages[2]; // will contain Java // log values console.log(var1, var2, var3, var4); // output: Javascript PHP Python JavaIn our attempts to extract the array elements into variables, we used array indexing to extract the array items from the array and saved them in variables:

var1,var2,var3, andvar4. This technique is very common and works very well. However, ES6 Javascript has a better way of handling such assignments.The ES6 Javascript introduces a very compact way of assigning array elements to variables without repetitive array indexing. With this approach, we can extract array elements and assign them to variables, all in just a single expression or statement. Consider the following code listing:

JavaScriptlet languages = ['Javascript', 'PHP', 'Python', 'Java']; // extract array elements into defined variables let [var1, var2, var3, var4] = languages; // log values console.log(var1, var2, var3, var4); // output: Javascript PHP Python JavaThe expression

[var1, var2, var3, var4] = languageson line 4 is called destructuring assignment. The expression declares multiple variables and maps them to the elements in thelanguagesarray in the same order.Think of the destructuring assignment as simultaneously declaring multiple variables,

var1,var2,var3, andvar4, and then unpacking the elements of thelanguagesarray into these variables. During unpacking, the values of thelanguagesarray elements are extracted into the declaration variables in the same array indexing order.For example, since

var1has index0, it will correspond withlanguages[0], and therefore its value will beJavascript. Sincevar2has index1, it will correspond withlanguages[1]and therefore its value will bePHP, andvar3, with index2, will have the valuePython, and so on..Now compare listing 3 to listing 2. If you are not already familiar with destructuring assignment in Javascript, then I bet you are beginning to love this programming construct, considering its compactness and the cleaner code it offers.

But that is not all. There are a lot that can be done with array destructuring, and we will cover them in this post. For example, destructuring assignment enables us to selectively extract specific elements of an array into variables and ignore those we do not need.

Destructuring Assignment Syntax

Before we dive deeper into array destructuring, it is important to understand the basic syntax for destructuring assignment. We will consider this basic syntax for both arrays and objects. The discussion on object destructuring is extensiviely discussed in a separate post, and can be accessed at Javascript Object Destructuring.

When extracting data from an array, the destructuring declaration variables need to be enclosed in square brackets:

[]. For example:JavaScript// In array destructuring, declaration // variables are enclosed in brackets: [] let [var1, var2, var3] = ArrayData;The names enclosed in brackets are variables into which we want to store the extracted values from the array. Therefore, these names must conform to Javacript variable naming considerations.

If we need to destructure values from an object, we use braces (square brackets),

{}, to enclose the declaration variables into which we store the extracted values:JavaScript// In object destructuring, declaration // variables are enclosed in braces: {} let {var1, var2, var3} = ObjectData;From the discussions so far, we can identify that the general syntax for destructuring arrays and objects are very similar, as shown below:

JavaScriptlet [] = ArrayData; let {} = ObjectData;Thus, when destructuring an array, we use brackets,

[]to enclose the variables in the destructuring declaration expression. For object destructuring, we use braces,{}, to enclose the declaration variables.In the discussions that follow, we will delve deeper into array destructuring. We consider javascript object destructuring in a separate post.

Array Destructuring

The ES6 Specification introduces array destructuring assignment through which we can assign the elements of an array to multiple variables in just a single statement. This eleminates the need to index the array elements one at a time in order to get the element values we need, as done in listing 2.

For example, given that we have an array of countries as shown below:

JavaScript// array declaration const countries = ['Ghana', 'Canada', 'United States', 'Germany']; const var1 = countries[0]; const var2 = countries[1]; const var3 = countries[2]; const var4 = countries[3];Using array destructuring statement, we can rewrite listing 7 as the following:

JavaScript// array declaration const countries = ['Ghana', 'Canada', 'United States', 'Germany']; // extract individual array elements into variables const [var1, var2, var3, var4] = countries;Line 5 is an array destructuring statement. This statement declares the variables

var1,var2,var3,andvar4, and then initializes them to the elements of the initializer array,countries. The elements in the initializer array are assigned to the variables by mapping each variable in the destructuring declaration to an element in the initializer array in the same order.To understand this better, think of the destructuring declaration

[var1, var2, var3, var4]as an array. Then variablevar1has index0and so maps tocountries[0],var2has index1and so maps tocountries[1],var3has index2and so maps tocountries[2], and so on; These mappings and extraction of values are done by Javascript so that we do not need to assign the elements in thecountriesarray one at a time with array indexing. With destructuring assignment, we are able to do all at once.Separating Variable Declarations from Assignment

In destructuring assignment, we are not mandated to always declare new variables for the assignment. Existing variables can be used in the destructuring declaration to assign values from the initializer array. An example is shown in the following code listing:

JavaScript// array declaration const countries = ['Ghana', 'Canada', 'United States', 'Germany']; // declare target variables let var1, var2, var3, var4; // extract individual array elements into variables [var1, var2, var3, var4] = countries; // log the values console.log(var1); // var1: Ghana console.log(var2); // var2: Canada console.log(var3); // var3: United States console.log(var4); // var4: GermanyThe variables

var1,var2,var3, andvar4are declared separately on line 5. Then on line 8, we use array destructuring statement to assign the initializer array elements to the already declared variables.As can be seen, we group the variables that we want to assign values in brackets, and then assign them to the initializer array. Javascript will automatically map the variables to the initializer array in order, and extract the values from the initializer array elements into the variables.

Variables Unmapped to Initializer Array Elements Are

undefinedWe have indicated that in an array destructuring statement, Javascript maps each item in the destructuring declaration array to items in the initializer array. However, if an item in the declaration array does not map to an item in the initializer array, then the value of that variable is

undefined. This happens when the number of variables in the destructuring declaration array is more than the number of items in the initializer array.Consider the following code listing:

JavaScript// array declaration const languages = ['PHP', 'Java', 'Javascript']; // destructure the array into variables const [var1, var2, var3, var4] = languages; // log value of var4 console.log(var4); // output: undefinedObserve that there are four destructuring declaration variables:

var1,var2,var3, andvar4. However, The initializer array,languages, has only three items.In destructuring the initializer array,

var1maps tolanguages[0],var2maps tolanguages[1], andvar3maps tolanguages[2]. However,var4does not map to any element in thelanguagesarray. The result is thatvar4is declared as a variable without an initializing value, similar to a variable declaration like the following which will haveundefinedas its value:JavaScript// declaration of variable without initializing value const var4;Thus, the value of a variable in the declaration array which is not mapped to an element in the initializer array will be

undefined.Setting Default Values for Variables

When destructuring an array into variables, we can set default values to be used when the value of a variable is

undefined.For example, in the previous section, we indicated that if a variable in the destructuring declaration array is not mapped to an element in the initializer array, then its value will be

undefined.If we like, we can provide a default value which should be used if the value of a variable is

undefinedafter the array destructuring. To do this, we assign the default value to the variable in the declaration array:JavaScript// array declaration const languages = ['PHP', 'Java', 'Javascript']; // destructure the array into variables const [var1, var2, var3, var4 = 'Python'] = languages; // log value of var4 console.log(var4); // output: PythonIn the destructuring of the array on line 5,

var4does not map to any item in thelanguagesarray and therefore should have its value to beundefined. However, on this same line, we assign a default value tovar4. The default value will be used if the value ofvar4isundefinedafter destructuring.Default values can be assigned to multiple variables in the destructuring declaration array. However, these default values are only used if the value extracted from the initializer array is

undefinedor when the variable has no mapping in the initializer array. For example:JavaScript// array declaration const languages = ['PHP', 'Java', 'Javascript']; // destructuring declaration array const [var1 = 'C#', var2 = 'C++', var3 = 'C', var4 = 'Python'] = languages; // log values console.log(var1); // output: PHP console.log(var2); // output: Java console.log(var3); // output: Javascript console.log(var4); // output: PythonOn line 5, we have set default values for all the variables in the destructuring declaration array. When mapped to the initializer array, we can observe that the values that will be extracted from the

languagesarray forvar1,var2, andvar3are notundefined. Therefore, the corresponding values in the initializer array are used rather than the default values.var4which is not mapped to an element in the initializer array, and expected to beundefined, will use the default value set in the declaration array.Let’s deliberately change the vaue of the first element in

languagesarray toundefined:JavaScript// array declaration const languages = [undefined, 'Java', 'Javascript']; // destructuing declaration array const [var1 = 'C#', var2 = 'C++', var3 = 'C', var4 = 'Python'] = languages; // log value of rust variable console.log(var1); // output: C# console.log(var2); // output: Java console.log(var3); // output: Javascript console.log(var4); // output: PythonAfter re-running the code, we should expect the value of

var1to be the default value set in the destructuring declaration array. This is becausevar1, which maps tolanguages[0], will have its value beingundefined, and therefore the default value instead gets assigned tovar1.Skipping to Selectively Extract Values

Sometimes, we may not need all the data that is contained in a given array. We may need the value of only one or a few of the array elements. If the array elements that we need aren’t contiguous, especially not at the beginning, then that will imply that we skip those that we do not need and extract those that we need.

Consider an initial array data below:

JavaScript// array declaration const countries = ['Ghana', 'Canada', 'United States', 'Germany'];Let’s suppose we are only interested in getting the values of the second, third and fourth array elements. In the pre-ES6 era, we will use array indexing to access the values, such as in the following code listing:

JavaScript// array declaration const countries = ['Ghana', 'Canada', 'United States', 'Germany']; const var1 = countries[1]; const var2 = countries[2]; const var3 = countries[3];With ES6 array destructuring, we can skip values by omitting variables names in the declaration array. To skip the first array item in the initializer array, we will omit the variable name from the declaration array. The comma is however important. It is an indication that we intend to ignore extraction of the value at that index.

JavaScript// array declaration const countries = ['Ghana', 'Canada', 'United States', 'Germany']; // ignore first item, and extract the rest const [, var2, var3, var4] = countries;Take a careful look at line 5. In the destructuring declaration array, there is no variable name specified before the first comma. We can identify that the position of the first item in the declaration array is blank, signalling that we intend to skip the mapping of the first array element in the initializer array.

Let’s again suppose we intend to extract only the second and fourth elements from

countriesarray. Since we want to ignore the first array element (index0), and the third array element (index2), we will not provide any variable names at the indexes we intend to ignore in the declaration array:JavaScript// array declaration const countries = ['Ghana', 'Canada', 'United States', 'Germany']; // ignore first and third items, and extract second and fourth const [, var2, , var4] = countries; // log values console.log(var2); // output: Canada console.log(var4); // output: GermanyNow what if we intend to extract only the last element from

countries? Again, we will not provide variable names at the indexes we intend to ignore:JavaScript// array declaration const countries = ['Ghana', 'Canada', 'United States', 'Germany']; // ignore first three items, and extract the last const [, , , var4] = countries; // log values console.log(var4); // output: GermanyOn line 5, the first comma skips the first element in

countries, the second comma skips the second element incountries, and the third comma skips the third element incountries.var4, then, maps tocountries[3].Swapping Values of Two Variables

Javascript array destructuring construct enables us to easily swap the values of two variables without the need to explicitly declare a third variable.

Before array destructuring was introduced in ES6 Javascript, you will declare a third variable as a temporary storage space in order to swap the values of two variables. The following code listing is a reminder of how it used to be done:

JavaScript// variables declaration let var1 = 50; let var2 = 80; // we need a temporal variable to store one of them const temp = var1; // swap values of var1 and var2 var1 = var2; var2 = temp; // log variables console.log(`var1=${var1}`); // output: var1=80 console.log(`var2=${var2}`); // output: var2=50With array destructuring, we can swap the values of two variables in just a single statement. This is done by changing the order of the variables in the declaration array and the initializer array. The following code listing is an example:

JavaScript// variables declaration let var1 = 50; let var2 = 80; // swap values of var1 and var2, [var1, var2] = [var2, var1]; // log variables console.log(`var1=${var1}`); // output: var1=80 console.log(`var2=${var2}`); // output: var2=50Observe line 9 carefully. We use the two variables that we want to swap their values in the declaration array and the initializer array. You should notice that the order of the declaration array items and the initializer array items are in opposite order.

In the declaration array,

var1is declared as the first item followed byvar2. Then in the initializer array,var2appears beforevar1. This means that we have interchanged the order ofvar1andvar2in the declaration array and the initializer array. In fact, this is the only single statement we need in order to swap their values, nothing more. After running the code, you should see that the values of these two variables have been swapped.Using Rest Syntax to Assign Remaining Values

Sometimes, we may need to extract specific elements into separate variables and then extract the remaining elements into some other variable. We can achieve this by using the rest operator introduced in ES6 javascript.

The rest operator is a three consecutive dots, (

...), operator, which precedes a variable in a destructuring declaration. It used to pack the rest, or remaining values of an iterable, such as an array, into the variable preceded with the rest operator.Consider the following code listing:

JavaScript// array declaration const countries = ['Ghana', 'Spain', 'France', 'Germany']; // extract first item into africa, then pack the remaining into europe const [africa, ...europe] = countries; // log values console.log(africa); // output: Ghana console.log(europe); // output: ['Spain', 'France', 'Germany']On line 5, the variable

africamaps tocountries[0]. The rest operator,..., preceding the variableeurope, that is,...europe, means that the rest of the elements, starting from the index mapping of where the rest operator is used, should all be packed into the variable preceded with the rest (...) operator.Thus, after destructuring,

europewill be an array containing the rest of the elements of thecountries, starting from the indexing mapping ofeurope(countries[1]) to the initializer array,countries.Considering another example, we can decide to extract the first two items and pack the rest in a different variable:

JavaScript// array declaration const countries = ['Ghana', 'Spain', 'France', 'Germany']; // extract first and second, then pack the rest in different variable const [ghana, spain, ...rest] = countries; // log values console.log(ghana); // output: Ghana console.log(spain); // output: Spain console.log(rest); // output: ['France', 'Germany']Using Spread Syntax to Expand Array Elements

The Javascript spread syntax is an expression that expands an iterable data, such as array, string, or object, into individual elements separated by commas. Like the rest syntax, the spread syntax also uses three consecutive dots, (

...), preceding an iterable variable to expand the iterable data into individual elements separated with commas.For example, to spread the elements of an array, we precede the array variable name with the spread operator, (

...). An example is shown in the following code listing:JavaScript// array definition const data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; // spread the array items console.log(...data);On line 5, we precede the array variable name,

data, with three consecutive dots (...). This expands the array into individual items separated by commas. The effect is that line 5 expands to the following call:JavaScript// ...data expands the array elements, separated by commas console.log(1, 2, 3, 4, 5);It is important to understand that passing an array as argument to a function call and spreading an array as argument to a function call are not the same. Hence, in the following code listing, the calls to the

logmethod of theconsoleobject are not the same:JavaScript// array definition const data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; console.log(data); // output: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] console.log(...data); // output: 1 2 3 4 5On line 4, we pass the array as argument to the

logmethod without preceding it with the spread operator. In this case, we are passing only one argument to thelogmethod. This, logsdataas array in the console.On line 5, we precede the array with the spread operator. This expands the array by spreading and separating the individual array elements with commas. Thus, after spreading the array, we are actually passing five arguments to the

logmethod.With the basic understanding gained so far, we should look at other code logic in which the spread syntax can be used.

Cloning An Array Using Spread Syntax

When we assign an array to another variable, the two variables become arrays pointing to the same array data. For example:

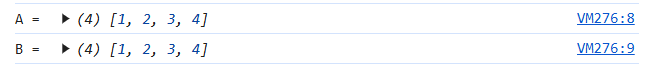

JavaScript// initialise array let A = [1, 2, 3, 4]; // assign A to new variable B let B = A; // log values console.log('A = ', A); console.log('B = ', B);As expected, both

AandBwill have the same values.

However, if we modify an element in

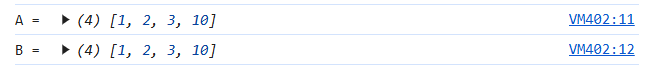

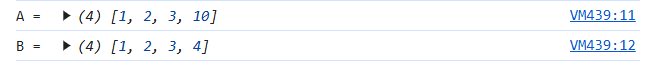

A, it will affect the values inB:JavaScript// initialise array let A = [1, 2, 3, 4]; // assign A to new variable B let B = A; // modify fourth element in A A[3] = 10; // log values console.log('A = ', A); console.log('B = ', B);On line 8, we modify the value of the fourth element in

A. However, this also updates the value of the fourth element inB, as shown below:

This happens because

AandBhave the same reference to the array data.We can use the ES6 Javascript spread syntax to easily clone the values of one array into another so that they will not reference the same array data. Rather than assign

AtoB, as we did on line 5 in listing 29, we will spread the elements ofAto initialize a new array which will be assigned toB:JavaScript// initialise array let A = [1, 2, 3, 4]; // assign A to new variable B let B = [...A]; // modify an element in A A[3] = 10; // log values console.log('A = ', A); console.log('B = ', B);On line 5, we set B to a new array that we initialize by spreading the elements

Awithin brackets,[]. This makes A and B have different references to array data, although they have the same values. An update to arrayAon line 8 does not affect arrayB, as shown in the following log output:

Thus, array

Ais a clone of arrayB. It should however be noted that this approach only creates a shallow copy of the source array.Concatenating Arrays

The spread syntax can also be used to concatenate two arrays. Before ES6, it was common to use the concat method of an array to concatenate two arrays. With ES6, we can use the spread syntax to achieve same.

Suppose we have two arrays, given in the following code listing:

JavaScript// array declarations const A = [1, 2, 3, 4]; const B = [5, 6, 7, 8]; // concatenate A and B const C = [...A, ...B]; console.log(C); // output: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]On line 6, we use the spread syntax to expand arrays

AandB. The effect is that a new array is initialized with its content being the values of both arraysAandB, and assign the generated array toC.Destructuring Array in Function Arguments

If a function accepts arguments in its call, and we have the values to be passed to the function in an array, there is no need to use array indexing to set the argument values. If the ordering of the array elements correctly map to the function parameters, we can use the spread syntax to spread the argument values.

For example, suppose we have the following function which has three parameters:

JavaScript// function definition function getVolume(width, length, height) { return width * length * height; }Suppose also that we have the values to be passed to the function in an array with correct mapping of the array elements to the parameters:

JavaScript// object shape data [width, length, height] const data = [3, 5, 4];Without array destructuring, we will pass the values to the function by indexing the array:

JavaScript// object shape data [width, length, height] const data = [3, 5, 4]; // calculate object volume let volume = gettVolume(data[0], data[1], data[2]);With array destructuring, we can spread the array elements when calling the function:

JavaScript// object shape data [width, length, height] const data = [3, 5, 4]; // calculate object volume let volume = getVolume(...data);As can be seen, using the

spreadsyntax involves less typing when compared to accessing the values with array indexing.Destructuring Array in Function Parameters

Traditionally, when an array is passed as argument to a function, we access the values of the array in the function by using array indexing to retrieve the individual array elements. For example, suppose we have a function that calculates the volume of an object based on values passed to it as array:

JavaScriptfunction getVolume(arrData) { const width = arrData[0]; const length = arrData[1]; const height = arrData[2]; // calculate and return volume return width * length * height; }Rather than use array indexing to retrieve the values into variables, we can use ES6 array destructuring construct to destructure the array parameter into individual variables without the need to access the values with array indexing. But before we see how this is done, let’s understand what happens when we pass a value as argument to a function.

Suppose we have a function that accepts a value in its call, such as the following:

JavaScriptfunction someFunction(PARAM) { return PARAM * 2; }As we know, we will call the function by passing a value to it as an argument:

JavaScript// call the function someFunction(ARG);When the function is called, the value of

ARGis assigned to the variablePARAMdeclared in the function’s signature. This implies that the function call leads to assignment ofARGTOPARAM:JavaScriptPARAM = ARGNow suppose ARG is an array,

[1, 2, 3], and we pass it as argument to the function, this results in the assignment of the array toPARAMdeclared in the function signature:JavaScriptPARAM = [1, 2, 3];But in our early discussions on array destructuring, we indicated that we can destructure an array into different variables, such as the following:

JavaScript[width, length, height] = [1, 2, 3];With this understanding, we can rewrite

arrDataingetVolume()function by replacing it with destructuring declaration variables:JavaScriptfunction getVolume([width, length, height]) { // calculate and return volume return width * length * height; }Thus, if a function accepts an array as an argument, then we can destructure the array parameter into declaration variables directly in the function header without the need for array indexing to retrieve the individual values into separately declared variables.

Destructuring Nested Arrays

We can apply our understanding of array destructuring so far to destructure an array within an array. As we will soon see, that is a very easy task, though it may seem daunting at first encounter. We will take step by step approach to better your understanding of nested array destructuring.

First, let’s assume we have the following nested array:

JavaScriptconst numbers = [0, [1, 2, 3]];We can identify that the array

numbershas two elements. The first element,numbers[0], has the value0, and the second element,numbers[1]has an array, which is[1, 2, 3].Our task is to extract all the numerical values into variables. We will name the variables after the number we want to retrieve, such as

one,two,three, etc. Let’s see how we can do this with array destructuring.First, let’s observe again that the

numbersarray has two elements. Suppose we destructure the array into two variables,AandB:JavaScriptconst numbers = [0, [1, 2, 3]]; // destructure into variables const [A, B] = numbers;In this code listing,

Amaps tonumbers[0]which has the value0, andBmaps tonumbers[1]which is an array:[1, 2, 3]. SinceBis an array, we can further destructure it into additional declaration variables. But since we already know thatAhas the value0, lets replace it with variable namezerowhich is its numerical value that we extract, and then continue from there:JavaScriptconst numbers = [0, [1, 2, 3]]; // destructure into variables const [zero, B] = numbers;Recall that

Bmaps tonumbers[1], which is an array:[1, 2, 3]:JavaScriptB = [1, 2, 3];We can now destructure

Binto additional declaration variables with the names of the values in the array:JavaScriptconst [one, two, three] = BWe can replace

Bwith the declaration variables:[one, two, three]. Hence, on line 4 in listing 45, we can substitute[one, two, three]in place ofB:JavaScriptconst numbers = [0, [1, 2, 3]]; // destructure into variables const [zero, [one, two, three]] = numbers; // log the values console.log(zero, one, two three); // output: 0 1 2 3Using array destructuring syntax, we have been able to destructure both the outer array and the inner array of

numbersinto distinct variables.Let’s further test our understanding of nested array destructuring with another challenge by updating the

numbersarray to the following:JavaScriptconst numbers = [0, [1, 2, [3, 4]]];We can identify that the

numbersarray has two elements. The first item,numbers[0], has the value0. The second item,numbers[1], has its value to be an array, which is[1, 2, [3, 4]]. Further, we can identify thatnumbers[1][2]also contains an array which is[3, 4].Going by the approach discussed earlier, we can destructure the values in the

numbersarray into variables as shown in the following code listing:JavaScriptconst numbers = [0, [1, 2, [3, 4]]]; // destructure into variables const [zero, [one, two, [three, four]]] = numbers; // log the values console.log(zero, one, two, three, four); // output: 0 1 2 3 4Javascript array destructuring syntax is not only elegant but also a time-saving approach. In just a single statement, we have been able to extract values of array elements, event nested ones, into distinct variables.

Wrapping Up

Javascript array destructuring is a programme technique introduced in ES6 Javascript which makes it possible to unpack an array and store the individual elements into variables. This can be done in just a single statement without the need to index the array to extract the values.

For example, given the following array:

JavaScript// array declaration const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4];We can use array destructuring assignment syntax to extract all the values from the array in just a single statement:

JavaScript// array declaration const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]; // extract values const [one, two, three, four] = numbers;The declaration assignment syntax on

line 5declares variablesone,two,three, andfour, and then maps each variable to thenumbersarray in order. In this case,onemaps tonumbers[0],twomaps tonumbers[1],threemaps tonumbers[2], andfourmaps tonumbers[3].If we do not need all the values from the initializer array, then we can skip specific values in the initializer array by ommiting variable names that should map to the elements we want to skip. For example, if we want to skip the first element in

numbers, then we will not provide any variable name in the declaration array:JavaScript// array declaration const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]; // ignore first element const [, two, three, four] = numbers;Observe that there is variable name before the first comma, indicating that we want to skip this mapping into the

numbersarray.If we want to skip the first and second elements, then following will do:

JavaScript// array declaration const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]; // ignore first and second elements const [, , three, four] = numbers;Sometimes, we may choose to extract specific value and pack the remaining ones into another variable. We can pack the remaining elements into a variable using the rest operator, (

...). For example:JavaScript// array declaration const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]; // extract first element, and pack the remaining into different variable const [one, ...others] = numbers; console.log(one); // output: 1 console.log(rest); // output: [2, 3, 4]In this code listing,

onemaps tonumbers[0]. The rest operator in frot ofothersimplies that starting from the current mapping, the remaining ones should all be packed intoothersvariable.We can even use array destructuring syntax to swap values of two variables. For example:

JavaScriptlet first = 10, second = 20; // swap their values [first, second] = [second, first]; // log the values console.log(first); // output: 20 console.log(second); // output: 10We can extend array destructuring syntax to destructure array parameters in functions:

JavaScriptfunction getTotal([var1, var2, var3]) { return var1 + var2 + var3; } const data = [10, 20, 30]; // get total let total = getTotal(data);Other operations that can performed with Javascript array destructuring include concatenation and shallow cloning of arrays. It can also be used to simplify extraction of values from nested arrays.

-

Understanding React useRef Hook

React

useRefis a hook that allows a function component to create a reference to a value and track its state between component re-renders. This is made possible because arefobject is able to persist its value so that it will not lose track of the value it references during component re-render. The reference can also be used to update the value that is being tracked.In addition to preserving values between re-renders, the

useRefhook is also used to create references to DOM elements and access their values or perform manipulations on them. For example, we can create reference to form input elements and extract their values after the user submits the form.In contrast to state variables,

refobjects are mutable. This implies that we can directly modify the values tracked by arefobject without the need for a special function. Updates torefvalues do not trigger a re-render of the containing function component, making them very efficient.In this post, we will demistify React

useRefhook with clear examples to better understand its capabilities and usage.Table of Contents

What is the use of useRef Hook?

Basically, React

useRefhook is used to create a reference to a value and preserve its state so that the value will not be lost when the function component re-renders. Additionally, it can be used to keep reference to a DOM element and retrieve or manipulate its properties such as content, appearance, etc.To better understand what we mean by preserving the state of a variable, lets’ look at the general design of a javascript function.

Traditionally, creating a value in a javascript function involves a variable declaration statement such as the following:

JavaScriptfunction logCallsCount() { // initialise counter variable let callsCount = 0; }Any updates to values initialised within the function, such as the value of

callsCountin listing 1, are retained as long as the function is still running. In other words, the function will remember the state of all variables declared within it as long as it has not exited:Consider the following code listing:

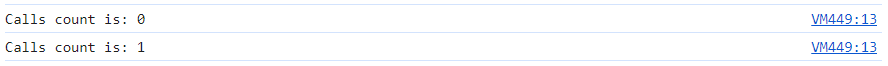

JavaScriptfunction logCallsCount() { // initialise counter variable let callsCount = 0; console.log(`Calls count is: ${count}`) // update calls counter callsCount += 1; console.log(`Calls count is: ${count}`) } // call the function to log calls count logCallsCount();A single call to

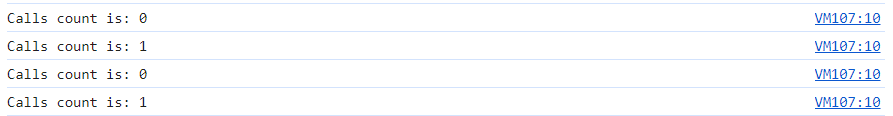

logCallsCount()online 12will produce the following in the console, which is exactly what we expect:

A general design of javascript functions, and in most programming languages, is that when a function completes its task and exits, the values of its variables are lost. Subsequent function calls will not remember the values of the variables in the previous calls. The values of the variables are reset when the function is called again and begins execution.

The following code listing calls

logCallsCount()twice.JavaScript// call the function to log calls count logCallsCount(); logCallsCount();The output of the code is shown below:

In the first call to

logCallsCount(), the value ofcallsCountwas1before the function exited. When the second call tologCallsCount()begins execution, it does not remember that the value ofcallsCountwas1when the first call tologCallsCount()exited. Therefore,callsCountis reset to the value0before being incremented by1. Hence, in each call tologCallsCount(), the same values are logged to the console.In modern React applications development, function components are widely used. When part of the application UI needs to be updated, React calls the function component to refresh and update the UI, a process commonly referred to as re-render. Thus, a function component can be called multiple times to perform UI update. This re-render of components causes local variables to be reset to initial values, losing any values they contained before the re-render, as demonstrated earlier.

To address this challenge, React uses hooks such as

useState,useReducer, anduseRefhooks to create a reference to a value and track its state so that its value will not be lost when the function component re-renders. In this post, we will focus on how to preserve values and access DOM elements withuseRefhook. The section on understanding useState hook tackles how to preserve and update values withuseStatehook.Creating a Reference with useRef

To create a reference to a value that can be preserved between component re-renders, or access a DOM element, we first need to import

useReffrom React:JavaScriptimport { useRef } from 'react';Once imported, we can create a reference variable by calling

useRef():JavaScriptlet clicksCount = useRef();In the above code listing, we declare

clicksCountas a reference variable and initialize it with a call touseRef(). As indicated earlier, this givesclicksCountthe ability to preserve the value it references so that when the function component in which it is defined re-renders,clicksCountcan remember its state from the previous render.useRefis a hook and therefore its usage must comply with the rules of hooks in React. For example, initialization of arefobject withuseRef()must be done at the beginning of the body of the function component.Mostly, it is appropriate to set an initial value when we declare a variable. For example:

JavaScriptlet clicksCount = 0;We can similarly set an initial value when we declare a

refvariable in React application. To do this, we pass the intial value as an argument touseRef():JavaScriptlet clicksCount = useRef(0);Just as we can assign values of any javascript type to a variable, we can also assign any value such as

number,string,array,object, etc by passing it touseRef():JavaScriptlet numberRef = useRef(20); let stringRef = useRef('Hello React'); let arrayRef = useRef( ['React', 'Javascript'] ); let objectref = useRef( {library: 'React', language: 'Javascript'} ); let undefinedRef = useRef(undefined); let nullRef = useRef(null);If we do not pass an initial value to

useRef(), then the value of the reference variable will beundefined.Now that we know how to initialize a reference variable, let’s compare a regular javascript variable declaration with a React reference variable declaration:

JavaScript// declaration of regular javascript variable let callsCount = 5; // declaration of React reference variable let clicksCount = useRef(5);As can be seen, creating a

refvariable in React isn’t much of a pain. We only need to set therefvariable touseRef(), while passing an optional initial value as argument touseRef(). Other than this, the two declarations are syntactically close.Ref Variables are Objects

A

refvariable is actually an object which contains a single property namedcurrent. This is because a call touseRef()returns an object, with the optional initial value set as value to thecurrentproperty:JavaScript{ current: initialValue }Whereas we can access the value of regular javascript variable directly, we can only access the value of a

refvariable through itscurrentproperty:JavaScript// declaration of a ref variable let clicksCount = useRef(0); // access the value tracked by the ref variable console.log(clicksCount.current);As can be seen, we are able to access the value referenced by the

refobject through thecurrentproperty.Ref Objects are Mutable

Unlike state variables initialized with useState() which must be treated as immutable,